Promise and Peril

The potential impacts of universal preschool

Story by Clarise Larson

Photos by Michael Martello

Illustrations by

Ella Musgrove

Missoula Democratic Senator Shannon O’Brien has spent 25 years of her life teaching kids. She has a doctorate in Educational Leadership. She’s a mother. She believes in basic human dignity. She believes child care is a basic need in Montana.

In the 2021 legislative session, O’Brien introduced a bill that would establish high-quality child care business development grants. It died.

O’Brien introduced a bill that would generally revise laws related to preschool programs in Montana. It died.

O’Brien introduced a bill that would provide child care scholarships. It died.

In fact, all of her 2021 proposed bills to further child care aid in Montana died.

Montana is one of just six states without publicly funded and provided child care, leaving a majority of low-income Montana families with no option for high-quality voluntary universal preschool programs, unlike the other 44 states that do. But that could soon change.

In April 2021, President Joe Biden announced a $200 billion bill on education funding that will direct the funds toward universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds across the country as part of a national partnership. If fully implemented, the White House estimates it will save the average family $13,000 annually and benefit 5 million children.

In simple terms — think free care for any child 3 to 4 years old, no matter the circumstances. Along with the free aspect, all care centers across the country will be teaching the same curriculum for the kids in the care provided as stated in the proposal.

“The basic — basic — needs of having spaces that are safe and appropriate for children are a huge issue right now,” O’Brien said about the child care crisis happening in Montana.

O’Brien said in past years Montana has taken big steps in ensuring quality child care — whether it’s in-home, center-based, or school-based, but the main issue is lack of space available and the low wages for child care workers.

“It’s unlivable. Who wants to go into child care when they’re making $8 an hour with no benefits working from eight in the morning to six every night?” – Shannon O’Brien, Missoula Senator

“It seems to be a Republican versus Democrat issue at the expense of our families, children and our economy; and I honestly don’t understand why,” O’Brien continued. “We know that at-risk children who get high quality, early care and education are significantly less likely to be arrested for a violent crime.”

Children who did not participate in the preschool program were 70% more likely to be arrested for a violent crime by age 18, according to the Economic Opportunity Institute.

O’Brien said the lack of statewide provided child care in Montana is not seen as an issue in the legislature despite the lack of care available.

“There is not a consensus in the legislature that we need child care. That’s the uphill battle we’re dealing with,” she said.

O’Brien said she hopes some change can be made because right now she considers Montana to be in an urgent child care crisis.

“What is a government doing if we’re not helping the people?” O’Brien said.

In Montana, 57% of households said finding affordable child care is a challenge, according to a report published by the Montana Department of Labor & Industry and the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis in 2019.

“Everyone knows that 12 years is not enough today,” Biden said at his “American Families Plan” address in April of 2021. “The days of our nation failing to support and invest in the future of our babies and toddlers are over.”

The proposal of universal preschool offers a great resource of care for families in need, but in Montana’s landscape, where the child care system is falling apart, what will happen to the already existing child care providers?

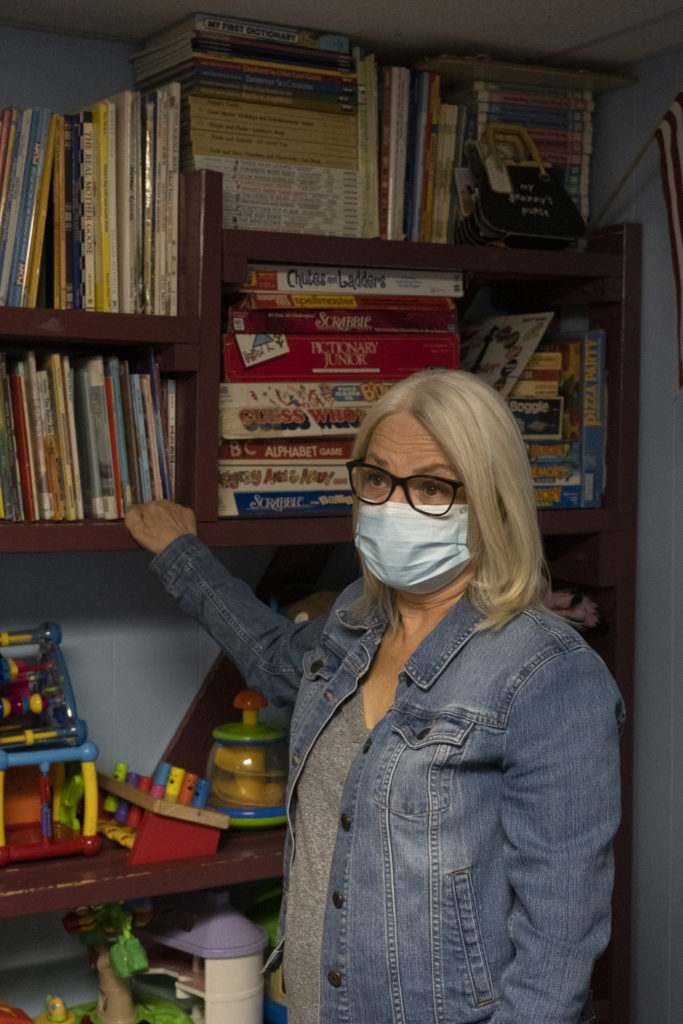

Liz Van Nice Family Daycare sits along Walnut Street in Missoula, Montana, shaded by two broad trees in the front lawn.

A door on the side of the house leads down to the three-room daycare. A wall with multiple-sized diapers faces the door. There are labels on everything: A “yellow wall” label hangs from the yellow wall. Stacks of toys, puzzles and colorful drawings line the walls of each room. Abundant beaming colors make the basement daycare seem brighter than the sun shining outside.

Liz Van Nice, 66, sits in her red cushioned rocking chair, the crinkles around her eyes evidence of her smiling beneath her mask. Despite the smile, her feet kick the rocking chair back and forth at what seems like an unnatural speed and her hands twiddle every few seconds.

“I do feel that [universal preschool] is going to have an effect on us,” Van Nice said.

Van Nice is worried about the bill because her livelihood is already being threatened due to the child care crisis. In past years, she was able to ask a reasonable charge to a set number of families that would be her only clients. It was steady pay, day in and day out. Now, she is rotating between multiple children to try and accommodate as many families as she can, but the prices keep rising and she said it’s hard to justify asking for more.

In December 2020, a family put down a $500 deposit to ensure their child would be able to start at her daycare at the beginning of October.

Between 2017 and 2019, 60% of preschool-aged Montana kids were not enrolled in any kind of early childhood program. SOURCE: Kids Count Data Center.

As nine months went by, not only did she painfully send back the deposit, in the same week she gave the heart-wrenching news that she would have to let go of almost half her clients and the income they bring to her.

It’s not just Van Nice who is affected, it’s the families who can’t find child care because there is nowhere to go or the costs are too high.

According to a study published in 2020 by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana, the average loss to household income because of child care costs for families with children between 0 to 5 years of age is $5,700 annually. Furthermore, 58% of Montana’s families with children age 1 to 5 are stay-at-home parents. For those who have jobs, 62% experienced time missed from work, according to the study.

Van Nice has provided child care to two generations of families in Missoula for 36 years, and while she hopes that will continue, she worries the evergreen effects the White House boasts about universal preschool will actually compound the current child care crisis.

Now Van Nice can only legally hold three children per working adult at her facility. She has been struggling for months to find workers and has come up dry. In order to keep multiple families afloat, she has been rotating among children to give as much care as possible.

If Van Nice loses her 3- and 4-year- old clients, she will be forced to raise the price for younger children significantly to make a survivable income and continue her business.

“You can only have so many [children] — three per provider under the age of 24 months. I can’t afford to hire somebody at that rate. Rates are going to skyrocket for parents, so if people can be home to be with the little ones — they will,” Van Nice said. “It’s going to snowball.”

The stress has made her feel sick, she said. For the first time in nearly four decades, she will be legally required to pay her only employee more money than she herself will take in from the business.

This is the first time in her 36-year-long career she has doubts that this profession will provide a livable income to her and her family. She no longer sees how providers are going to be able to stay in this profession and make money at the same time.

“This has never happened to me before,” she said.

Beyond the financial and career issues she faces, Van Nice worries universal preschool isn’t going to be good for the needs of children aged 3 to 4.

Van Nice acknowledges there is a child care crisis in Missoula, but she also said she doesn’t think universal preschool is the best option for the children’s wellbeing and development. Veteran child care providers like Van Nice worry the needs of children will not be met by making a large-scale preschool and child care system while also having to face the reality that 60% of preschool-aged Montana kids were not enrolled in any kind of early childhood program, according to a study done by Kids Count Data Center between 2017 and 2019. But Van Nice also doesn’t have an answer on how to stop the child care crisis from growing more out of control than she sees it now.

“I don’t think it’s good for a child to have structure all day long, and I know some parents will not want their children to be put into a big classroom with a big group of kids at 3 years old,” Van Nice said.

Van Nice has spent her whole life dedicated to children as a caretaker, friend and healer — but what happens when healers like her are forced to leave the field? Universal preschool might not be everyone’s favorite option, but it might be the only one.

Dr. Rachel Severson is a professor at the University of Montana with a doctorate in developmental psychology and expertise in children’s social-cognitive development. Her research is primarily with children 3 to 9 years old.

Severson said that, in principle, she supports the idea of universal preschool. But in reality, she has no way to know what will be implemented yet. Her biggest hope as a psychologist is that universal daycare provides high-quality care and consistency in the caregivers and facilities across the country.

The talk around having a curriculum for young children has been a sore spot when it comes to universal preschool. From her knowledge in the field, Severson said her recommended type of learning for preschool age children involves interactive, physical, knowledge-based learning that eventually moves into conceptual knowledge.

“When we talk about curriculum, it’s not like some worksheets. It’s having kids doing things, physically manipulating objects and moving,” Severson said.

Longitudinal studies — studies that assess a group of individuals repeatedly over a period of time — have shown factors in early childhood that are associated with outcomes in adulthood. Severson said, for example, preschoolers’ executive function skills, which are responsible for things like impulse control, planning and turn-taking, strongly predict their future academic performance, peer relationships and professional success. And, importantly, preschoolers’ executive function skills can be improved through early childhood learning.

“The disparities that we see in kids, later on, we can see through their developmental trajectory and see where they started to diverge. For so many skills, they happen really early,” Severson said. “There’s an opportunity early on to set kids on the right course for their social development and cognitive development but when that isn’t happening, that becomes the point we start to see the divergence that plays out over their lifetime.”

Severson said many of her friends ask her questions about her work in hopes to get some insight on the best way to help their kids. She said she gets asked time and time again if she could make one change to help kids broadly, what would it be? She always has the same answer.

“My friends say ‘Oh, you’re gonna say health care,’ but actually, no. I think it’s high-quality childhood education and care for all of pre-K. When we know that is quality, across the board, every child benefits,” Severson said.

“Not to say that health care isn’t important though,” she added with a chuckle.

The effects of universal preschool are widely unknown, but the cognitive needs of children are not.

Caitlin Jensen, executive director of the statewide office of Zero to Five, a nonprofit that works to build partnerships with child care systems to serve children and families all across Montana, said she thinks this universal preschool can be something great for Montana’s children.

“I think what’s being proposed is high-quality care, at the root of it,” Jensen said.

Zero to Five works to advance public preschool and access to affordable quality child care for young children.

However, Jensen said if the proposed preschool system is implemented, the nonprofit would offer extra specialization that would focus on child care while still remaining in the general education degree field.

For Montana, this extra endorsement won’t come as a shock.

“There’s an early childhood Higher Education Consortium, which is a partnership between the University of Montana, UMT and tribal colleges. Lots of the early education work to make sure that teachers are prepared, whether they’re going into work in child care, a facility in at Head Start or in a school district,” Jensen said.

“So, what’s being proposed in this federal legislation is that there would be a lot of alignment when it comes to teacher preparation,” Jensen said.

In 2016, the Department of Education offered a grant to Montana that provided a minimal preschool program along with the educational endorsement for teachers. Though it is not enough to fix the statewide child care crisis, Jensen said the groundwork for universal preschool in Montana has already been established through that grant.

Jensen said preschools will be built in response if the bill gets passed, but part of the proposed $200 billion bill on education will also go to daycares and other child care facilities. The idea behind the spreading of funds is to provide the same guidelines of preschool learning, but offered in different settings.

That means child care would still be available at in-home daycares, but also through school-district programs in school-based settings. It allows child care to be applied in a variety of settings across Montana.

But with this plan also comes extreme measures of coordination. Jensen said although the proposed program will give funding to child care providers outside of the built preschools, there is no guarantee the subsidies for outside care will be enough.

Jensen said the bottom line is Montana does not have the subsidy programs to ensure child care providers are financially stable.

“If parents are having to pay more and more, there’s a higher likelihood that they won’t keep their kids in care, because they can’t afford it,” Jensen said. “It’s a vicious cycle.”

Jensen said the thing most people don’t know about the possible bill is it really won’t financially burden the average taxpayer in the U.S.

“The current proposal doesn’t increase taxes on people making under $400,000. So the majority of Americans and Montanans don’t really need to be concerned about paying more in taxes,” Jensen said.

In Montana, taxpayers lost $32,036,000 due to inadequate child care, according to the 2020 study by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research. Not only is the current system burdening the taxpayers, but the Montana economy has had major negative effects caused by inadequate child care across the state.

The cumulative loss of household income across Montana to inadequate child care in 2019 was $145,146,000. The average cost to businesses because of parents’ child care problems is $54 million annually.

If nothing changes, the economic burden to the Montana economy will go from $145 million lost from households to an estimated $907 million by 2028.

Pointing out the painting hanging above the knee-high table surrounded by chairs three times smaller than the average, Van Nice smiles at the out-of-line colorings and unidentifiable drawings her kids proudly made. But she remains uneasy.

“I’m really upset for the families that I’m having to let go because there’s nowhere for them to take their children,” she said.

Whether or not government-implemented child care will help the people of Montana, Van Nice’s daycare doors will remain open to the few children she can still care for — until she is forced to leave the job that has become a part of her identity.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Copyright © [hfe_current_year] [hfe_site_title] | Powered by [hfe_site_title]