Welcoming Them Home

The return of native species is healing the land

of the Aaniiih and Nakoda

Story and photos by Sarah Mosquera

On a cloudy night in September, a single spotlight cuts through the darkness. Jessica Alexander, a 38-year-old field biologist, drives her gray Toyota Tundra across the Snake Butte pasture. Her dog, Kouva, sits silently in the back while Alexander scans the horizon beyond the truck.

“Sometimes I think I left her behind because she’s so quiet back there,” Alexander says laughing.

With the driver’s side window down, her left hand controls the spotlight suction-cupped to the roof of her truck. She sweeps the light back and forth, searching. Within the darkness, the spotlight catches the gleam of two emerald eyes. A long rectangular metal trap protrudes from a prairie dog hole. Inside the trap, a small ferret hisses.

“Black-footed ferrets live in prairie dog holes after they eat them,” Alexander explains. “They run from hole to hole and as they stick their little heads out, it’s easy to spot their bright green eyes.”

Within the darkness, Alexander searches the ferret for a microchip, then quickly takes him to base camp, an old camper near the entry gate. She anesthetizes him on the fold-out dinner table and adds a chip to the base of his neck. This allows her and other scientists to monitor the animal and document which vaccines it has received and when. Alexander administers the F1-V vaccine to protect the ferret from the plague. F1-V is only made in Colorado and has a two-week shelf life, so she must estimate how much she needs before going into the field.

Alexander is the owner of Little Dog Wildlife LLC. She works closely with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and the Fort Belknap Indian Tribes to help monitor and protect the prairie ecosystem.

“The sylvatic plague was introduced by rats who came over on ships in the 1900s,” Alexander explains. “It’s transferred through fleas and will quickly wipe out an entire prairie dog colony.”

Since black-footed ferrets are dependent on prairie dogs as a food source and for shelter, a bout of the plague would be detrimental to the highly endangered species.

Once found throughout the Great Plains, the black-footed ferret population steadily declined since the beginning of the 20th century due to agricultural expansion, government-led poisoning campaigns and the sylvatic plague. After 30 years of reintroduction programs, the population is slowly increasing, but still less than 400 black-footed ferrets live in the wild.

In 2013, the local tribes of Fort Belknap partnered with the WWF to reintroduce the endangered species back to Snake Butte, but it wasn’t their first attempt. In 1997, the ferrets were introduced to the same pasture, but were soon wiped out by the sylvatic plague. Beyond administering vaccinations, Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife department dust the prairie dog holes to protect them from fleas.

“Prairie dogs are a keystone species,” Alexander explains. “Without them this habitat couldn’t exist. In order to protect the ferrets, we must protect the prairie dogs.”

Rising from the prairie, Snake Butte stands prominently within a sea of gold. The northern face of the butte is scarred and damaged from past extractive activity. Nearly a century ago, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) quarried the butte and hauled away columns of granite to construct the legendary Fort Peck dam. Along the butte’s southern face, the grunts of more than 800 buffalo can be heard as they wallow on prairie dog mounds: the tribes’ first reintroduction success story. Buffalo, scientifically called bison, returned to the Snake Butte pasture in 1974 thanks to the Aaniiih and Nakoda tribal members who live on the land.

In partnership with organizations like WWF, the Fort Belknap tribes have pioneered the way for wildlife reintroductions within the Great Plains ecosystem. Beginning with buffalo and moving on to black-footed ferrets and swift foxes, each native species is a necessary puzzle piece for a healthy prairie. The Aaniiih and Nakoda people are healing their land by bringing back the animals that belong there.

On a windy autumn day in late September, George Horse Capture Jr. drives his white Ford F-150 through the Snake Butte pasture. As the truck creeps along the butte’s eastern perimeter, prairie dog whistles fill the cab.

“You drive through this particular area and there’s so much life,” Horse Capture says. “The prairie dogs singing around, the buffalo grunting, the antelope and the coyotes running.”

The Aaniiih elder looks stylish in Wrangler blue jeans and a decorative Pendleton overcoat. Considered a “knowledge keeper,” the importance of the butte and its inhabitants is deeply ingrained in him. “Our knowledge is there’s a big rattlesnake that lives here. That lives inside [of the butte],” Horse Capture says.

According to local legend, Snake Butte is home to a monstrous snake that has made its home deep within the crevice of the butte.

“[The snake’s] got a lot of powers,” Horse Capture says. “Both tribes believe. My people say, stay away … It is not to be trifled with. Even good power. Good power, bad power, they’re not to be trifled with.”

Both the Aaniiih and Nakoda tribes have local legends about the snake who inhabits the depths of the butte. Tribal members approach the landmark with respect and caution. The butte has long been a sacred area used by many Indian tribes for prayer, fasting and gathering medicinal plants.

“The butte is a landmark,” Horse Capture says. “It could be spotted by Indians while they were traveling throughout the plains…They would stop here to pray or to fast. Many tribes respect this place.”

In the 1930s, the USACE began plans for one of Montana’s biggest construction projects, the Fort Peck dam. To construct the highest dam along the Missouri river, the engineers needed extremely durable rock. By 1931, they had spotted the impressive landmark. The massive granite columns of Snake Butte were exactly what the USACE needed for the dam being built over 100 miles away. They blasted the northern face of the butte, causing the prominent columns to crumble. A temporary railroad snaked through the prairie to haul away the riprap. Five years later, a black and white image of the dam’s spillway by photographer Margaret Bourke-White served as the first cover of Life magazine for a story about the dam’s construction.

Snake Butte is never mentioned in the story.

After construction of the dam finished, the world celebrated the marvelous new structure along the Missouri and the success of Roosevelt’s New Deal. There was a definite irony in the festivities. Bourke-White’s powerful images show men and women celebrating the project’s success in front of a sign that reads, “No Beer Sold to Indians.” Snake Butte still stood boldly, now with a prominent scar and surrounded by the rubble left behind by the USACE. The blasts left the butte in a damaged state and the rail line — cutting through the otherwise pristine grasslands — was abandoned.

Remnants from the extraction remained on the Snake Butte prairie until 2003 when the tribes created the Fort Belknap Brownfields Program. They partnered with the Environmental Protection Agency and Technical Outreach Services for Native American Communities (TOSNAC) to remove the rubble and any potential toxins left behind at the quarry site. According to official documentation, “The highest priority was to return [Snake Butte] to a natural state.”

The Fort Belknap Brownfields Program offered environmental training at the Aaniiih Nakoda College, helping the locals get jobs at the clean-up site. The program trained locals from Fort Belknap in environmental clean-up to protect workers from any hazardous waste left behind at the quarry site. Slowly the team removed rubble and riprap from the quarry site and then began deconstructing the metal rail lines from the prairie. Now, nearly a century later, the Snake Butte pasture is no longer covered in remnants of the collapsed columns. Water from a spring near the northwestern face runs clear, and many locals visit the site regularly to gather drinking water.

“It seems to be okay again now,” Horse Capture said. “The water is tested regularly, and they haven’t found any toxins in there for a long time now.”

As Horse Capture turns his truck along the southern face of the butte, he sees more than 50 buffalo grazing in the pasture. The whistles of the prairie dogs are drowned out by grunts and snorts. A cloud of dust fills the air as a young female buffalo flops onto her back and rolls around on a prairie dog mound.

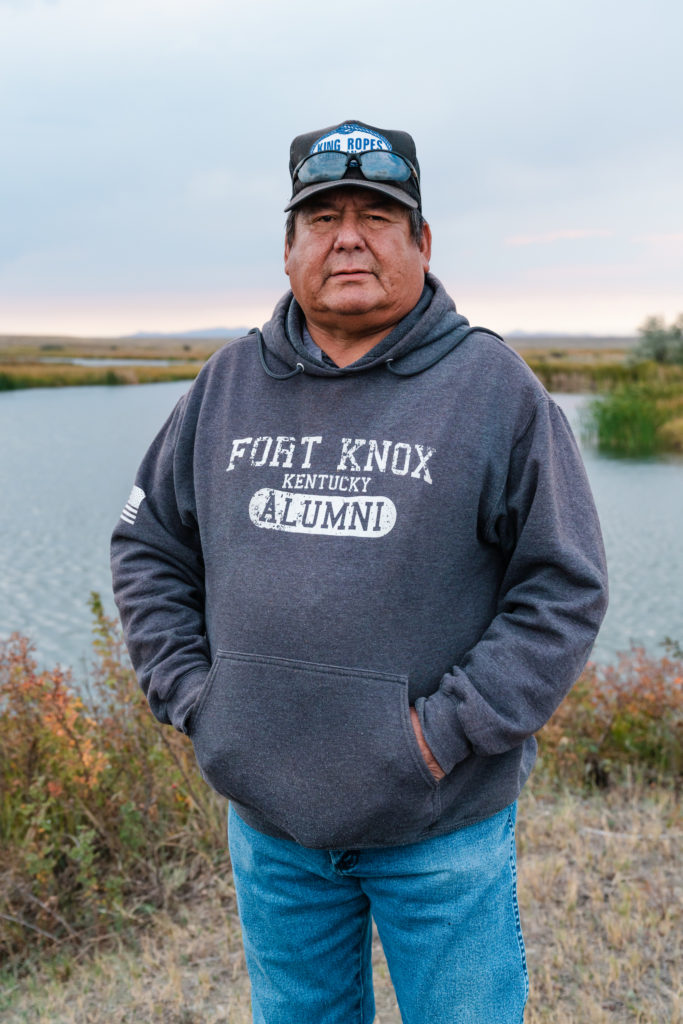

“I never get tired of this,” Aaniiih Councilman Mike Fox says while watching a swift fox through a pair of binoculars. “Every time we have one of these reintroductions, it’s like a family member is returning home. How could you get tired of that?”

Fox has been involved in many reintroduction projects on Fort Belknap, from the buffalo to the ferret to the swift fox.

“It just felt like the right thing to do,” he says. “This is where these animals belong. If we have an opportunity to bring them home, we should.”

In 2020 the tribes began a five-year conservation partnership with the Smithsonian Biology Conservation Institute to reintroduce swift foxes to their land. The goal of the partnership is to create a self-sustaining population on the reservation. Fox says it’s been more than 51 years since the swift fox lived on their prairie.

Swift foxes were declared extinct in Montana in 1969 and the remaining species in North America were divided into the northern population and the southern. As agriculture became more of a way of life in the state, grassland habitat was destroyed along with biodiversity. The beautiful chaos of the Great Plains ecosystem was replaced with militant rows of agricultural crops. As the habitat morphed outside of the invisible boundaries of Fort Belknap, species connectivity became more difficult to maintain. The foxes are far-ranging and by returning them to the Fort Belknap prairie, it will help to bridge population gaps. Species connectivity is essential to create a healthy swift fox population and ensure survival.

Beyond the ecological importance of each reintroduction, the animals help tribal members maintain a connection to the past. “Our people have always had a kit [swift] fox society,” Fox said. “The swift fox has important cultural significance for us. That society was created by our ancestors who lived on this land with the foxes.” By bringing the animals back to the Great Plains, tribal members are reconnecting to the land and healing alongside the ecosystem.

Fox spent 10 years working for the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council, where he helped tribes across the country bring buffalo herds back to their lands. In 1974, 27 buffalo were reintroduced to the Snake Butte pasture, now the herd is over 800 head. The Snake Butte herd is one of two on the reservation. The other, introduced in 2012, is further south and on the other side of the highway — those are genetically pure Yellowstone bison.

“I never cared about the DNA testing for the buffalo,” Fox said. “They’re not genetically pure but that’s not an important factor. It’s like the blood quantum. I’m 9/16th Indian, I’m still an Indian. It’s the same for those buffalo.”

Cristina Eisenberg, an Indigenous ecologist from Oregon State University, explains that bison evolved with the grasslands.

“Their hooves have formed in a way that prevents trampling of the grasses,” she said. “And they help make the grasslands more resilient to climate change by increasing biodiversity.”

Buffalo and prairie dogs are essential for healthy grasslands and are both considered keystone species because they change the ecosystem and create habitat for other animals. The prairie dogs trim down the prairie grasses, which encourages new growth and makes it easier for bison to digest. Though swift fox and black-footed ferrets are not considered keystone species, they are indicators of grassland health. Both species are important components of the Great Plains ecosystem. “The swift foxes are now back where they belong,” Harold “Jiggs” Main, director of the Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife department said. “Along with the buffalo and [black-footed] ferrets.”

Main has been director of Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife for over 14 years. He has been involved in every animal reintroduction on the reservation. Lately, Main has been receiving a lot of phone calls from conservation groups interested in working with them. In April, the tribes won the Parker/Gentry award for their rewilding efforts. The award is given out every year by the Chicago Field Museum to honor excellence in conservation biology. Main, much like Fox, is honored, but sees their efforts as doing what’s right.

“People keep wanting to talk to me, but I’m not the one doing all the work. The researchers from the Smithsonian are out there studying the foxes,” Main said. “Those scientists and the biologists here. They are the ones doing the hard work to protect these animals.”

Main hopes bringing the animals back to their land will inspire the younger generations to develop an appreciation for nature and the wildlife. With so much pristine wilderness within reservation boundaries, the opportunities for young people to become involved with conservation efforts are becoming more abundant. With field technician training available through a grassland restoration program and a specialized ecology degree available at the Aaniiih Nakoda college, young people are taking more of an interest in conservation and in protecting their land.

On a warm autumn day, beneath the shadow of Snake Butte, Fort Belknap tribal members gathered in the tall prairie grasses as WWF scientists prepared to release the black-footed ferrets. Among the crowd was a group of young children from the local White Clay Immersion School. As the cage door opened, the ferret tentatively poked its head out. It peered around at the onlookers before sprinting to a nearby prairie dog hole. The children cheered and raced after the ferret, eventually encircling the hole. Leaning forward, with their heads nearly touching, the children gazed into the dark tunnel searching for its new resident. Suddenly, the ferret sprang from the hole and barked a warning at the curious children.

“They all screamed and fell back like a blooming flower in fast motion,” Main laughs, while throwing his hands into the air. “It was good to see something like that for our youth because they’ll probably remember it forever. And then they might take the time to understand a little bit more about the ferrets.”